The design, construction, and real estate industries are overlooking a golden opportunity to revolutionize sustainability by rethinking commercial interior architecture. While efforts have largely centered on new, ground-up construction, the tenant improvement process remains a hidden culprit behind mountains of waste—both environmental and financial. With just a few strategic adjustments, the industry could dramatically reduce its carbon footprint while unlocking significant savings for building owners and tenants alike.

The impact

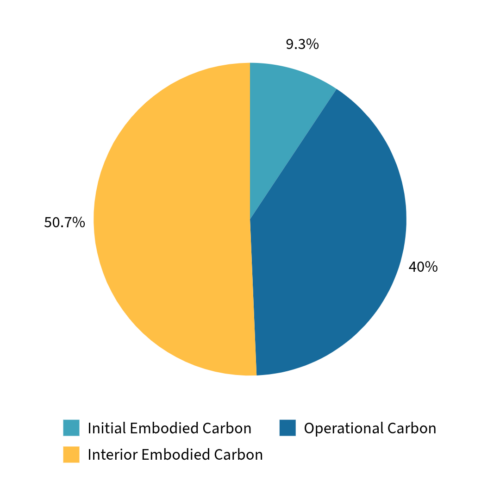

A building’s carbon footprint gives us a comparable metric to evaluate the impact of interior architecture on that building’s sustainability. The carbon footprint of a building is typically separated into its “operational carbon” and its “embodied carbon.” Operational carbon refers to the carbon emissions associated with day-to-day operation of a building. Embodied carbon refers to the emissions associated with the extraction, manufacturing, and transport of materials used in the construction of buildings.

While embodied carbon encompasses all the carbon from construction over a building’s lifetime, it should be separated further into the “initial embodied carbon” and “interior embodied carbon,” with the initial embodied carbon accounting for the carbon associated with the construction of only the core and shell of a building. If we look at the 50-year lifecycle carbon footprint of an existing building, we shockingly find that the interior embodied carbon can account for over 50% of a building’s carbon footprint.

The data

With the operational carbon emissions varying greatly from building to building – calculated based on several factors including the type of energy source and a building’s energy efficiency – we will have to make some reasonable assumptions. Assuming our commercial office building is in Seattle and was likely built between 1960 and 2010, we can use a range of 30 – 60kg CO2e/m2 per year as a benchmark. Calculated over a 50-year lifespan, these buildings will produce between 1,500 – 3,000 kg CO2e/m2 of operational carbon.

In 2017, The Carbon Leadership Forum at the University of Washington did a study evaluating the initial embodied carbon for existing buildings. It found that the initial embodied carbon of an existing building is typically less than 1000 kg CO2e/m2. Additionally, 50% of the buildings studied had an initial embodied carbon falling between 200 and 500kg CO2e/m2.

To calculate the interior embodied carbon, we must look at how the industry operates today. A building suite is remodeled in sequence with a new lease or a lease renewal, with the average lease lasting five years. Meaning that over a 50-year life span of a building, each suite will be remodeled approximately 10 times. If we use the numbers provided by RESET, the average commercial office remodel has an interior embodied carbon of about 190 kg CO2e/m2, then the lifecycle interior embodied carbon of a building is roughly 1900 kg CO2e/m2. We can clearly see that the interior embodied carbon can account for half of the lifecycle carbon footprint of a building.

So, what can we do?

The easiest way to lower an existing building’s interior embodied carbon is to limit the demolition of existing construction. Broadly speaking, there are three types of suites on the market – “as-is,” “refreshed,” and “shelled.” Tweaking the industry practices around how and when these suite types are prepped, remodeled, and marketed would not only reduce the environmental impact of interior remodels, but also stands to financially benefit both building owners and tenants.

An as-is suite is put on the market in close to the same condition that a previous tenant left it in when vacating. Since there is no demolition and no new construction prior to being put on the market, these spaces allow the tenant to determine what can be reused for their own purposes. The tenant’s design can take advantage of existing conditions to minimize the interior embodied carbon and lower the cost of construction on their remodel. For building owners, the up-front costs are very low, but these suites can be somewhat harder to market and sit empty longer, possibly resulting in a delay of rent revenue.

Refreshed suites refer to any built-out suite where some amount of construction has occurred prior to putting it on the market. This construction can range in scope from new carpet and paint to a fully furnished “plug-and-play” spec suite and is determined solely by the building owner. Refreshed suites can reuse existing construction to minimize their interior carbon footprint and are able to walk the middle line between marketability and cost with the assumption that little else will be remodeled once the lease is signed. While even the simplest scope for these spaces can add costs for a building owner (as compared to costs of demolition) and does not eliminate the risk of a tenant needing further alterations, these suites often lease faster and allow tenants to occupy more quickly with little to no cost to them. Since the refresh is up to the building owner’s discretion, they are able to balance the scope of the refresh with marketability.

Shelled suites are spaces where most if not all of the existing interior construction is removed prior to marketing the suite. While these suites are inexpensive and quick for building owners to create and allow tenants more design flexibility, they eliminate opportunities to reuse existing construction. This inherently drives up the interior carbon footprint. Additionally, there is little evidence to suggest that these shelled suites are more marketable, with reporting from CBRE suggesting that refreshed suites generally lease three months faster than shelled suites. For building owners, there is an adverse delay in rent revenue and an assumption of increased tenant improvement disbursements. For tenants, these shelled suites impose larger construction budgets and delays in occupancy.

By prioritizing as-is and refreshed suites over shelled spaces, the industry has a clear path to slash interior embodied carbon while reaping financial rewards. Eliminating the creation of shelled suites and embracing a reuse-first mindset isn’t just an environmental imperative—it’s a smart business move. Together, we can reshape how tenant improvements are approached, fostering a future where sustainability and profitability go hand in hand.

About the Authors

Emily and Amanda are co-owners of Studio Vibrant, a women-owned, women-led interior architecture and design firm focused on how to better serve our clients. Our combined 35+ years of expertise touches on a wide range of project types including workplaces, sports & athletics, amenities, and healthcare & biotech. We work with our clients and project teams to create thorough, thoughtful, and unique spaces that truly speak to the end users they serve. We believe every project should be one-of-a-kind, sustainable, and born of a collaborative process.